-

Shanda LodgeAbout UsHotel RatesLocationHow To Reach There

- Facilities

ReceptionLoungesRestaurantsSpa WellnessPoolRooms- Attractions

NatureHistoryArchaeologyArchitectureFlora Fauna- Activities

Culture ToursCamel Rides TrekkingDesert SafariYoga MeditationSand BoardingStargazingBedouin NightHot SpringWellness RecoveryBird Watching- Sightseeing

KHARGA Sightseeing

KHARGA Sightseeing Details

PARIS:

The old townThe old town of Paris is practically not visited by tourists; the few people who make it out here, use their time exploring the ancient slave city of Dush.

Should you have the time, Paris is actually quite interesting. It is filthy though, since it is mainly abandoned by its former inhabitants and taken over by goats. But some houses are still in use, and the ones not in use are in good condition. Should you be lucky enough to find an empty house with an open door, you have a chance to see how traditional life really was.

Some houses are decorated, and then they usually tell the story about the proprietors journey to Mecca, names and details are described with Arabic text, the means of transportation has been painted. A fine example just below.Dush: The wealthy slave metropolis 120 km south:

DUSH

The wealthy slave metropolis

Few of Egypt's sights are more remote than Dush, 125 km south of Kharga, deep into Sahara. The ruins of this ancient city overlooks a valley that was fertile some 1,500 years ago. Today only a tiny little village remains. But trunks of palms dot the sand in all directions.

The ancient name was Kysis, and Kysis was a wealthy city benefiting from slave trade between Sudan and North Africa. Its wealth is easy to spot. The city must have housed 10,000 inhabitants, the distance between the 1st century CE Roman temple and the later Christian basilica is a few hundred metres, an area packed with house ruins.

The slaves transported through the desert, along the Forty Days Road were mainly blacks, often Nubians. Slaves were highly treasured, and the most valuable were young Nubian women. They were said to have a cool skin no matter what the heat.

Inside the sacred

The last and smallest building of the temple was as always the holiest part. Here the divine figures lived, here the highest priests performed daily rituals. According to the world view of the locals, this was the place where the safety and prosperity of all of Kysis was preserved.

The inner building is almost intact. The columns stand as they used to, the roof is complete. But the wall decorations have not survived centuries of sand storms.

The casing of the roof is complete, and it is easy to climb up. I discovered that the temple of Dush will not survive big-scale tourism: the casing is porous and falls off when you walk across it.The temple

The temple of Dush (known as Kysis) was built in the 1st century CE, and dedicated to the gods Isis and Serapis. It has since 1967 been beautifully restored, and it also has a great location. It overlooks the all of the eastern valley below former Kysis. The temple appears to be unusually narrow, giving it a feeling of being long. There are two hypostyle halls, both with entrances in near perfect condition. On the photo below is seen the first entrance; the inscriptions are hardly touched by the near 2,000 years which has passed.

Most columns have been knocked down, but large pieces lie around. Note that the eastern side seems to have been without a wall, as allowing the fertile lands below to have been visible during during ceremonies.Christian basilica

The Christian basilica is the first you see when arriving at Dush. It lies on the highest point here, a place you would have imagined that the older Roman temple would have claimed. Despite its younger age, its condition is completely inferior to the temple.

But there is one interesting similarity with the temple, the basilica is also very narrow. During service it can hardly have houses more than 40-50 persons during service. Another similarity is more common; the church was also arranged with one room for the holiest, then a room for laymen, and a courtyard in front.

The basilica is made of mud-brick (second photo for close-up details). I could not see any traces of any casing, but that must have been the case. The mud-brick was not terribly good for paintings or other decorations.Remains of houses

There are more houses between the basilica and the temple complex than you will be able to count. There has been no or little excavation performed here, so it is difficult to decide whether there is much or little left of the house walls.

But it is clear that the architecture was not very different from what you see in the oasis villages that were used up until the Egyptian government moved in with their prefab concrete houses. Houses of Kysis (Dush) were quite small, built as close to one another as possible and streets were narrow.The Roman (Fortress at Dush ( Roman Era )

The very southernmost outpost of Kharga Oasis is marked by a Roman fortress known simply as el-Qasr (literally ‘the Fortress’), a mud-brick structure measuring about 30m by 20m. In Roman times a small garrison of troops would have guarded the fortress, but it is not known whether it was purely a military guard-post or if intended to control the trade route at the southern end of the Darb el-Arba’in.

Near to Dush, on a hill, is the site of the ancient town of Kysis, one of the oldest Roman ruins in Kharga Oasis. Once a border town commanded by a large garrison of Roman troops, it contains a mud-brick fortress (Qasr Dush) and two temples.

The area around Dush has been investigated since 1976 by French archaeologists of the IFAO who have found evidence of temporary occupation possibly dating back as early as the Old Kingdom (possibly Dynasty IV). On the slopes of the hill, Persian and Ptolemaic Period settlements have been identified and the earliest fortress which enclosed a rectangular area at the top of the hill was of Ptolemaic or possibly even Persian origin.

Abutting the Roman fortress on the eastern side are the remains of a sandstone temple, probably erected by Domitian, enlarged by Trajan and then partly decorated by the Emperor Hadrian during the 1st to 2nd centuries AD. The temple was originally dedicated to Osiris, who the Greeks transformed into Serapis and also to the goddess Isis. A monumental stone gateway fronts the temple and contains a dedicatory inscription by Trajan dated AD 116 as well as graffiti by Cailliaud and other nineteenth-century travelers.

In March 1989, during the excavation of a magazine complex on the west side of the temple, French archaeologists discovered a magnificent collection of artefacts, now known as the ‘Dush Treasure’ (Cairo Egyptian Museum). They first uncovered a linen-wrapped gilded statuette of Isis, a small bronze figure of Horus dressed as a Roman legionary, and a bronze figure of Osiris. Nearby, a large loose-lidded pottery jar which had been concealed by masonry, was found to contain a hoard of magnificent gold religious jewellery and ex-votos objects. These precious items had obviously been gathered together for safety and hidden in the jar during the 4th to 5th centuries AD. The religious treasure was of the highest quality craftsmanship and included a golden crown depicting the Roman god Serapis as well as bracelets and pendants of gold and semi-precious stones. These objects have provided scholars with valuable information about Roman worship in Egypt.

From the temple courtyards, many other artifacts have been unearthed, including pottery, coins, and ostraca. A large collection of demotic ostraca date from the Persian Period. Many were also written in Greek, appearing to be dated from the early 4th to 5th centuries AD and consist largely of receipts and payments for supplies for the Roman army but also include names of individual soldiers and civilians. -

About 5km north-west of Qasr Dush. An entire ancient village buried in the sand, with houses, fields, orchards, irrigation channels and even the hoof prints of bovines in the dried mud of a pond where the animals were watered. The site was a Persian and Roman settlement with a small mud-brick temple, although archaeologists have now confirmed occupation from the end of the Paleolithic Period. The excavations have so far uncovered a house to which a small temple of Osiris was attached. Hundreds of archival texts have been found, written in demotic on large ostraca, including one from the reign of Xerxes (Dynasty XXVII) – the first instance of this king’s name written in demotic – as well as Artaxerxes I and Darius II. The documents provide evidence of relations between the temple at ‘Ayn Manawir and Hibis Temple further to the south in Kharga Oasis.

Qasr el-Zayan Several guide books rate the Qasr el-Zayan fortress as in a very ruinous state. This is not entirely true, walls stand high, the centre of the temple is almost intact, and the setting is great. The main drawback is the original small size; you can cover it all in 5 minutes.

The temple was built dedicated to the go Amenebis, the local town god. It was built during the Ptolemaic period and restored under the Roman emperor Antoniunus. The local town here was known as Tchnonemyris which flourished for several centuries. The modest village here now tells nothing about the rich past.

This place is the lowest in the Kharga Oasis, 18 metres below sea level.Location : Near the main road, about 75km north of Dush towards Kharga City, are the ruins of Qasr el-Zayyan, one of the largest and most important ancient settlements in Kharga Oasis. It lies about 30km to the south of the city of el-Kharga and not far from the fortress of Qasr el-Ghueita.

Historical view : One of the chain of fortresses built during Ptolemaic and Roman times, the settlement was known in ancient times as Takhoneourit, which the Greeks called Tchonemyris, meaning ‘The Great Well’. The town was obviously of importance as a major water source in antiquity and would have been a place where travellers would stop for the night. Because of the availability of water in this part of the oasis, the town must once have been quite large and prosperous and surrounded by small farming settlements on agricultural land which constitutes the lowest part of the Kharga depression, at 18m below sea-level. It is here that the cemeteries of the ancient community are to be found.Within the walls there is a temple dedicated to the god ‘Amun of Hibis’, who was known to the Romans as Amenibis. This small sandstone was first constructed during the Ptolemaic Period, but was renewed during the Roman rule of Antoninus Pius (AD138-161) Inside the fortress enclosure were the living quarters of the Roman garrison and modern clearance by the Supreme Council of Antiquities have uncovered rooms containing kilns and hearths, a water cistern and a cache of Roman coins.

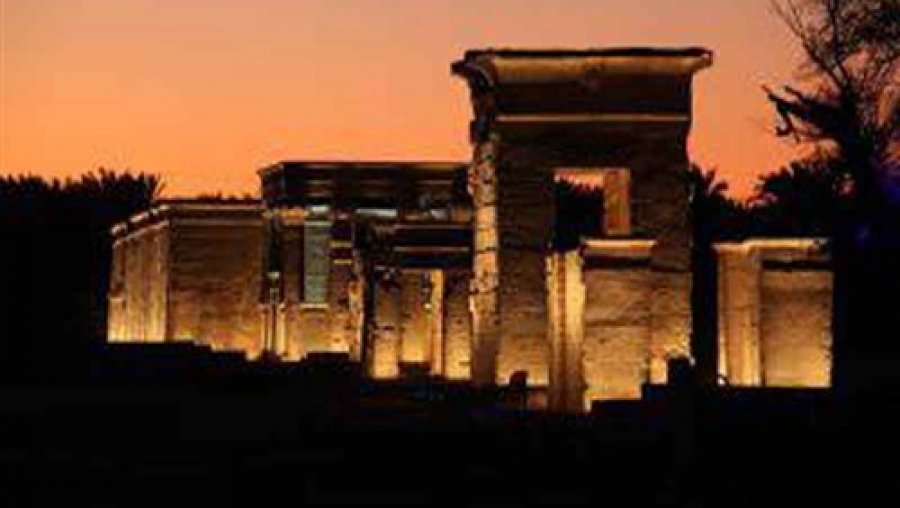

Sunset over the desert near Qasr el-Ghweita.

Location: A little to the north of Qasr el-Zayyan, is the magnificent hilltop fortress of Qasr el-Ghueita, which like the former site also contains a temple. The Arabic name of the mud- brick Roman fortress means ‘fortress of the small garden’, evidence that it was once part of a thriving agricultural community. The imposing fortress of Qasr el-Ghueita can be found 3km to the east of the main road and about 18km south of the city of el-Kharga,

Historical background : Long before the Romans came to Egypt, this settlement was called Per-Ousekh and is thought to have existed from at least as early as the Middle Kingdom, when it was famous for its wine. Texts in the New Kingdom tombs of the nobles at Thebes describe the excellent quality of the grapes from the vineyards of Per-Ousekh.

yellow sandstone temple within the Roman walls measures 10.5m by 23.5m and occupies about one-fifth of the space within the fortress. Its earliest parts are thought to date to the reigns of Ahmose II (Amasis) of the Persian Dynasty XXVII and Darius I of Dynasty XXVIII, though it was possibly begun by the Nubian rulers of Dynasty XXV on the site of an earlier sacred structure. The temple, dedicated to the Theban triad of Amun, Mut and Khons,. A pronaos with screen walls was constructed by Ptolemy III in a courtyard which fronts the temple.This leads to a hypostyle hall, richly decorated in Ptolemaic style with scenes of Nile gods .Decoration in the extant temple contains the names of Ptolemy III (Euergetes I),

Ptolemy IV (Philopator) and Ptolemy X (Alexander I). There is no suggestion of earlier decoration but it is thought that this hall may have been constructed by Ahmose II. To the rear of the offering room are three parallel sanctuaries for the cult statues of the Theban triad, with the largest, the sanctuary of Amun, on the right-hand side. These walls too are decorated but blackened by smoke and age.

Temple of Nadura

The Temple of Nadura is about 700 years younger than the one at Hibis, and belongs to the 2nd century CE and was built under Roman rulers. Few of Kharga's sights have been so badly treated by time as this, and except for the pieces of the wall, there is little to see here.

It is generally attributed to the god Amon, but the few remains of wall decorations represents musicians playing on percussion instruments and sistra. This indicates that a goddess was worshipped here.

Near the temple, a semi-troglodyte village lies. The inhabitants built a mud-brick houses, with cellars largely underground. The purpose of this sort of structure, found all over North Africa, was to escape the worst heat in summer time.Location: At Nadura, whose name means ‘The Lookout’, remains of a temple once enclosed within a Roman fortification are strategically perched high on a hilltop about 1.5km south of the centre of el-Kharga.

The settlement of Nadura is now buried and the two temples of the village are badly ruined, but the southern entrance wall of the main temple can still be seen on top of the hill. Thought possibly to be outposts of the large and well-preserved Temple of Amun at Hibis, 2km to the north-west, it is difficult to know to which deities these two temples were dedicated. The main temple was built during the rule of Hadrian and Antoninus Pius during the 2nd century AD..A Coptic church once stood within the space outside the temple and the whole structure was later reused as a Turkish fortress.

Temple of Hibis

This temple, named after the town that once existed here, is unique for Egypt in one respect. It is by far the largest and finest of temples from Egypt's 200 years under Persian rulers. It was King Darius 1 of the 6th century BCE who ordered it built, and dedicated to Amon. The temple was adorned by rulers over the following centuries, but the original style was always respected.

Today it is not available for closer inspection, as the main structure is swathed in scaffolding. It is planned to be relocated to a new location, close to the Bagawat Necropolis, but this will not be realized for many more years.

Should you be allowed to enter the area (it is guarded by tourist police, no tickets are sold) the kiosk in front of the main entrance (upper photo) is part of what was an avenue of sphinxes. The interior (visible through the gates) is noted for its beautiful capitals.Cultural history : is a Saite-era temple founded by Psamtik II which was erected largely by the Persians (Darius the Great and Darius II) during their rule over Egypt ca. 500 BC.

Name & Location : The temple of Hibis was once part of the ancient capital of Kharga Oasis, known as Hebet, meaning ‘the plough’, or Hibitonpolis (‘city of the plough’) to the Greeks. It is situated in a palm-grove where it dominates the desert road about 2km north of el-Kharga and is the largest and best-preserved temple of its period in the oasis. in a palm-grove.[7] There is a second 1st millennium BC temple in the southern most part of the oasis at Dush.[8]

Recent exploration by the local Supreme Council of Antiquities (2002) has unearthed a cemetery at the site which is thought to date from the Second Intermediate Period and New Kingdom, while excavations in an area to the south of the temple have revealed that the Christian era buildings dating to around AD350 were destroyed by a great fire. This indicates a very long period of occupation.

The earliest extant parts of Hibis Temple date to the reign of the Persian ruler Darius I, although it was probably begun during the Dynasty XXVI reigns of Psamtek II, Apries and Amasis II, or built on the site of an even earlier structure for which foundations were found by Winlock. The temple was constructed from local limestone blocks on the edge of a small sacred lake and dedicated to the Theban triad of Amun-Re, Mut and Khons. It was decorated by Darius I, and possibly Darius II, with additions by Nectanebo II and the Ptolemies, and a Christian church was constructed on the northern side of the portico during the 4th century AD.

It was Nectanebo I and Nectanebo II who surrounded the temple with a stone enclosure wall, so that it is now approached through a series of gateways leading to the inner parts. A sphinx-lined avenue led west from a quay on the edge of the lake along a paved processional way laid by an official of the oasis named Hermeias during the 3rd century AD. A massive sandstone gateway through an outer enclosure wall still stands almost 5m tall and was constructed during the Ptolemaic or Roman periods. Numerous inscriptions and decrees were written on the gateway – a kind of notice-board which has greatly contributed to our understanding of Roman rule in the oases. These include a variety of topics such as taxation, inheritance, the court system and rights of women, with the earliest dating to AD49.

The Dynasty XXX construction of the inner enclosure wall enclosed a monumental kiosk or colonnade with eight columns, which fronted the main part of the temple. Although thought to be built by Nectanebo I only the cartouches of Nectanebo II remain on the decoration.

A larger hypostyle hall, rather than the traditional pillared court, was added to the original temple by Hakor (Achoris) of Dynasty XXIX and it was this king who probably strengthened the foundations and buttressed the west wall against collapse, which had begun in the original structure soon after it was built..

The inner parts of the temple, probably constructed over the foundations of a New Kingdom shrine of Amun, illustrate the transition between New Kingdom and Ptolemaic architecture, showing that what we consider to be Ptolemaic inventions actually originated in the Saite or Late Period. There are several side-chambers and stairs lead up to the roof which contained an extensive complex of cult chambers dedicated to Osiris.

Hibis is the finest example we have in Egypt of a Persian Period temple .The temple contains a rich religious iconography and a wealth of theological texts in a very unusual style, perhaps the influence of a local style of art which until recent years has barely been studied..

A complete wooden codex from Hibis was purchased on the antiquities market in Luxor in 1906. The codex, now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, was written in Greek and contained two texts, the first a list of names and accounts and the second, dated circa 246-249AD, a report by a government official detailing a survey of water sources in the oasis.

Bagawat Necropolis

The Necropolis of Bagawat is a reminder of one of the most central battles of early Christianity; the dispute over the nature of Jesus. The 5th century bishop Nestorius was exiled to Bagawat (as the village was called) for having claimed that only one of Jesus' natures had suffered on the cross; the earthly nature, not the divine.

The large extent of the Necropolis of Bagawat is the result of the his and his supporters' exile. The tombs here are believed to indicate that worship of the dead was continued in a Christian style.

There are 263 mud-brick chapels climbing up a ridge, the oldest dating back two centuries before Nestorius, the last dating back to the 7th century.

Interiors of Bagawat

Most of the interiors of the chapels of Bagawat were probably without much decorations. And among the ones which were decorated, the hardship of time has been cruel. the walls of the interior is decorated with biblical scenes. The best of these is the Chapel of the Exodus, showing scenes from the Jews and Moses escaping from Egyptian troops. In the finest, the figures have been defaced by Muslim fanatics decades ago.Al-Bagawat: An ancient Christian cemetery at Al-Bagawat also functioned at Kharga Oasis from the 3rd to the 7th century AD. It is one of the earliest and best preserved Christian cemeteries

Location: About 3km from the centre of el-Kharga and 1km north of the Temple of Hibis is the early Christian cemetery of Bagawat.

Bagawat is perhaps the oldest major Christian cemetery in the world and has become a main tourist attraction for Kharga Oasis.

The cemetery consists of a vast expanse of domed mud-brick mausoleums and underground galleries dating back to the 4th century AD.

Two of the most outstanding and best preserved of the decorated chapels are named ‘Chapel of the Exodus’ and ‘Chapel of Peace’. Inside the Chapel of the Exodus, which is one of the earliest in the cemetery, the interior of the dome is decorated in two bands illustrating scenes from the Old Testament; Adam and Eve, Moses leading the Israelites through the Sinai desert in the Exodus, Pharaoh (Rameses II) and his armies, Noah’s ark, Daniel in the lion’s den, Jonah and the whale and several other biblical episodes. In the Chapel of Peace, similar themes are depicted on the dome, including the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary and others, each identified in Greek. The interior walls are also painted with many Byzantine frescoes of grape vines, peacocks, allegorical figures and inscriptions. The purpose of the Christian tomb-chapels, like their ancient Egyptian counterparts, was for the reverence of the deceased.

Nearby monuments

Gebel el-Teir

About 2km beyond the cemetery of Bagawat in an ancient limestone quarry in the foothills of, there are numerous graffiti inscribed on the faces of rocks and boulders. The graffiti, written in Demotic, Greek and Coptic, span over seven centuries and date from Ptolemy VIII through the Greek and Roman periods to the Coptic Christian era.

Tahunet el-Hawa

Standing far out on the open plain west of Bagawat, is a tall mubrick tower known as Tahunet el-Hawa, or ‘Tower of the Winds’. The structure is presumed Roman although it has never been properly investigated or dated by archaeologists. Measuring roughly 6m by 6m at the base and rising almost 12m in height,

The Fortress of el-Deir

Ed-Deir

Ed-Deir was a fortress that protected the shortest caravan route between Kharga and the Nile. It stands on the eastern extreme of the Kharga Oasis, at the foot of Umm el-Ghanayin Mountain.

It is made up of a fortress with 12 rounded towers, connected by a gallery. Only some of the rooms have survived, and are clearly marked by the long career of the fortress. Graffiti starting centuries ago, also include decorations of early 20th century airplanes.Location : The fortress-town of el-Deir, also known as Deir el-Ganayim, lies at the foot of the eastern escarpment about 20km north of el-Kharga, where it guarded the main desert route towards Farshut and the Nile Valley.

Historical background : It is one of the most impressive Roman fortresses in North Kharga.

The interior is now empty apart from a few rooms on the southern side of the courtyard and the plastered walls of these rooms still contain a wealth of modern graffiti left by British soldiers who were stationed nearby during the First World War, as well as many Arabic, Coptic and Turkish names. Although never excavated, the fortress is thought to date from the reign of Diocletian at the end of the 3rd century AD.

It is thought that the site was occupied from the Ptolemaic Period or earlier through to the 5th century AD, and was cultivated up to the 20th century when it was eventually deserted.The temple, about 1.5 km north of the fortress, is constructed from mudbrick, similar in plan to the temple at Qasr Dush and thought to date to the 2nd to 3rd centuries AD. It contains an antechamber with benches along its sides, a hypostyle hall, an offering chamber and vaulted sanctuary. The name el-Deir means ‘the monastery’, indicating occupation of the site in early Christian times, when the temple itself was transformed into a Coptic church and may have been the monastery from which the name derives.

Qasr el-Sumeria & Qasr el-Geb

Location : About 50km north of el-Kharga, Qasr el-Sumeria is a small unexcavated Roman fortress which was surrounded by a settlement now marked by a sea of pottery sherds strewn across the desert floor. The ruined fortress stands on low ground on the ancient desert route between Asyut and Dakhla, the Darb el-Arba’in, at the point where it enters the Kharga depression via the Ramia pass.

The mudbrick fortress, 14m square and 7m high contained several rooms, all of which have now collapsed.An extensive Roman cemetery is located further to the south of the settlement which contains rock-cut tombs as well as brick-lined tombs with vaulted ceilings.

Qasr el-GebLocation : As the most northerly Roman fortress of Kharga Oasis, Qasr el-Geb stands on a high-point of the desert only about 2km from Qasr el-Sumeria and is a replica of the latter structure. The fortress of el-Geb is visible from the main road.

Historical background: In Roman times Qasr el-Geb was the last source of water in the Kharga depression. Larger than its companion fort of el-Sumeria at almost 17m square and 11m high, the strategically situated structure probably served as a watchtower and beacon to control and guide travellers into and out of the oasis. All of the desert between the eastern and western escarpments is visible from Qasr el-Geb.

It is thought that Qasr el-Sumeria and Qasr el-Geb were probably constructed around the 5th century AD and were both re-used by the Turkish garrisoned army during the Ottoman Period.

Qasr el-Labekha

Qasr el-Labeka

The Qasr el-Labeka was built by the Romans, yet largely implementing traditional building techniques. It was on the old caravan routes, and in its heyday the surrounding area was green and and with water. Water was carried by an aqueduct that still stand, but which is silted up.

It lies along a seasonal river (wadi) on an escarpment. The outer walls are 12 metres high and quite imposing.

The location for this and the Ain Umm Dabadib is both part of the attraction and the reason why so few venture out here. The journey goes across real desert, and is only done by 4WDs, which arranged from tour operators in Kharga is expensive.Location: The fortress and settlement of Qasr el-Labekha lies in an isolated part of the desert around 12km west of the main Asyut to el-Kharga road and approximately 50km north of the city itself.

Description : The fortress of el-Labekha was constructed in a wadi at the base of the northern escarpment and served as a garrison, strategically placed to guard the intersection of two important ancient caravan routes from the north and the west.

Historical Background: An impressive brick-built temple, situated to the north of the fortress, was constructed on a natural outcrop which dominates the wadi. The temple, 12m square, contains three rooms and possibly dates from the 3rd century AD.

A second more ruined temple, to the north-west of the fort, was only rediscovered during 1991-92 by Adel Hussein of the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation. This temple was completed during the reign of Antoninus Pius and still contains some of its original painting. There is recent evidence that the temple may have been dedicated to Hercules (who also had a temple in his name at Bahariya) and later to a deified man named Piyris during the 3rd century AD.

Ain Muhammed Tuleib

Location : Remains of a late Roman settlement and fort can be found near the modern village of Ezbet Muhammed Tuleib, about 1km from the main road on the track leading to el-Labekha.

Ain Umm el-Dabadib

Ain Umm Dabadib

Ain Umm Dabadib is the sight of Kharga that requires the most effort to reach, crossing sand dunes. The former town here owed its wealth to being one of the last staging post before the caravans headed north.

Its history goes back to Roman times, and remains of temples from this period still stand. There are also ruins of churches outside the fortress walls. The original water cisterns and irrigation systems helped use the limited water resources as well as possible. An underground aqueduct system is still visible. It used to run for 15 km, and some of it still in use by local farmers. The original Ain Umm Dabadib was large, perhaps more than 200 km².Location: At around 40km north-west of el-Kharga, at the base of the northern escarpment, Ain Umm el-Dabadib is in a remote region of the oasis which lay on the Darb Ain Amur, the ancient route to Dakhla Oasis. Here, a small but impressive fortress once surrounded by a large well-populated settlement remains one of the most impressive sites in North Kharga.

Details : The site includes an Egyptian-style temple, a Christian church, several cemeteries and a vast irrigation system.

Historical Background : The fortress town seems to have been surrounded by a large area of cultivation, irrigated by a vast system of underground aqueducts. The five aqueducts so far discovered at Ain Umm el-Dabadib are by far the best example of such elaborate tunnels in Kharga Oasis, but more sophisticated than the Roman Qantas in the other areas and similar to the ‘foggara’ found in Libya and Algeria. The tunnels are also similar to those in ancient Persia, leading scholars to speculate that the irrigation system may date back to the Persian occupation of Kharga.

Several areas with Prehistoric remains have also been located at Ain Umm el-Dabadib. The whole plain is an ancient dried-up lake, or ‘playa’ where the action of sand and wind over the millennia can be seen in the shapes of the rocks. It is possible that the site was occupied sporadically from these early times, but its present importance is in providing valuable information covering the transitional period between Pagan and Christian Egypt.

Ain AmurLocation: Ain Amur is a tiny isolated oasis lying between Kharga and Dakhla, on a wide ledge half-way up the north-western cliffs bordering the Abu Tartur Plateau, which outlines the Kharga depression. Caravans travelling along the Darb Ain Amur between Kharga and Dakhla would have stopped at this spring (fed by fresh surface-water) to break their journey and it became the site of a quite large and important settlement. The well, with its ancient stone water-trough, still contains water today although it is now choked by weeds.

Historical background : Originally the site was enclosed by a thick irregular-shaped wall, but only two short sections still remain. The most impressive remains are those of a Late Period stone temple at the northern side of the settlement. The temple has sandstone walls and a roof constructed with limestone slabs and faces the main entrance to the settlement. It originally contained three chambers and an inner sanctuary, but only the eastern and western walls remain. There are a few original decorations and numerous Coptic and Arabic graffiti still to be seen but which provide little information to help with precise dating of the structure. One example, on the exterior western wall, includes a badly-preserved relief of a ram-headed Amun, an unidentified winged figure and part of a male wearing a kilt.

Along the Darb Ain Amur there is Prehistoric, Greek and Arab material similar in style to graffiti, rock-drawings and inscriptions recorded elsewhere in the Western Desert, confirming that the track was used by travellers of all periods. Old Kingdom graffiti has been found which provides new evidence of activity from that period in Kharga Oasis, possibly linking it with Old Kingdom settlements in Dakhla.

Qasr el-Ghweita

Standing inside the holiest of the holy, looking out, you actually see right through the fortified village and into the valley below. Impossible to catch on photo, but really a nice view.

Around the temple there was a village that must have housed a couple of hundred persons. Some buildings are in about as fine condition considering the age of more than 1,500 years.About 20 km south of Kharga is the temple Qasr al-Ghweita built between 250 and 80 BCE. It was dedicated to the Theban triad Amon, Mut and Khonsu.

According to some guide books, it is in a very ruinous state. This is fortunately not true. The 10 metre high walls are nearly intact, the houses have high walls still standing and the temple is about as complete as any other popular ancient destination in Egypt. Even large parts of the surrounding village can be seen.Qasr el-Zayan

Several guide books rate the Qasr el-Zayan fortress as in a very ruinous state. This is not entirely true, walls stand high, the centre of the temple is almost intact, and the setting is great. The main drawback is the original small size; you can cover it all in 5 minutes.

The temple was built dedicated to the go Amenebis, the local town god. It was built during the Ptolemaic period and restored under the Roman emperor Antoniunus. The local town here was known as Tchnonemyris which flourished for several centuries. The modest village here now tells nothing about the rich past.

This place is the lowest in the Kharga Oasis, 18 metres below sea level.Kharga Cultural Museum

Location : Kharga Heritage Museum is situated in the centre of el-Kharga, on Sharia Gamal Abd el-Nasser and is open daily from 8.00am to 4.00pm.

For an overview of antiquities found in Kharga and Dakhla Oases, nothing could be better than a visit to the recently constructed Kharga Museum, one of the latest in the Egyptian Ministry of Culture’s regional museums plan. Built from local bricks to echo the style of early Christian architecture seen at Bagawat, the museum houses artefacts ranging from the Egyptian Prehistoric Period right through to the Islamic Era.

In Pharaonic times, the oases were important provinces, with large settlements, since they were Egypt’s front line of defence against invaders from the west and south. Many funerary items from pharaonic tombs are displayed, including outer parts of the Dynasty VI tomb of Im-Pepi, discovered by the French Mission in Dakhla Oasis and a false-door stela of Khent-Ka, also from the Old Kingdom.Roman presence in the Western Oases is represented most of all, especially in the form of glass, ceramics and coins found in excavations by the many teams who have worked here in recent years. One of the most exciting finds is from Dakhla Oasis, where the Canadian Mission, directed by Professor Tony Mills discovered a set of wooden ‘notebooks’, known as the Kellis Wooden Panels. These important documents written in Greek and Coptic contain lists of accounts and payments in kind by tenant farmers during Roman times. They also give details of marriage contracts and letters, giving us tremendous insight into productivity and everyday life in the oases.

The second floor houses Christian and Islamic artefacts from the oases, including many religious items as well as articles of cultural interest from the more recent heritage of the region. Artefacts include textiles, icons, books and coins. There are also many folk items which reflect the customs and traditions of the New Valley.

Lastest News

-

DAKHLA The remote and genuine oasis

Shanda Lodge

-

Yoga Safari

Shanda Lodge

-

Sahra Oasis Grand Tour + Cairo & Luxor

Shanda Lodge

-

Shanda Recipe for Spa & Wellness

Shanda Lodge

-

SHANDA SUNSET

Shanda Lodge

Email to friend

You need to Login to add item in your wish list

- Facilities

Clear

Clear