-

Shanda LodgeAbout UsHotel RatesLocationHow To Reach There

- Facilities

ReceptionLoungesRestaurantsSpa WellnessPoolRooms- Attractions

NatureHistoryArchaeologyArchitectureFlora Fauna- Activities

Culture ToursCamel Rides TrekkingDesert SafariYoga MeditationSand BoardingStargazingBedouin NightHot SpringWellness RecoveryBird Watching- Sightseeing

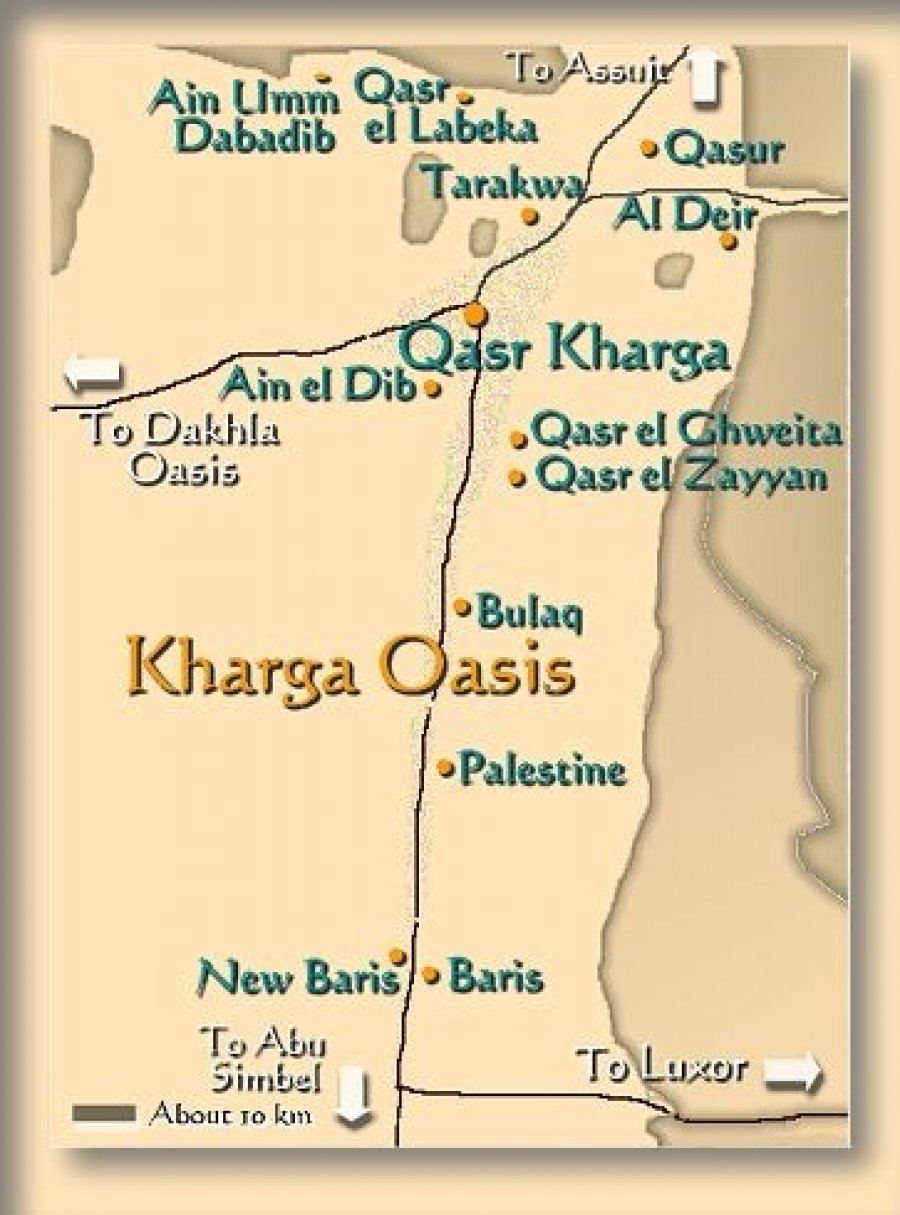

KHARGA

KHARGA Details

Name: also known as Al-Kharijah, (meaning the outer oasis)

Location : is the southernmost of Egypt's five western oases. It is located in the Libyan Desert, about 200 km to the west of the Nile valley, and is some 150 km long. It is located in and is the capital of New Valley Governorate.[1]

Area : this oasis, which was known as the 'Southern Oasis' to the Ancient Egyptians is the largest of the oases in the Libyan desert of Egypt and "consists of a depression about 160km long and from 20km to 80km wide."

General Information : Kharga is the most modernized of Egypt's western oases. The main town is a highly functional town with all modern facilities, and virtually nothing left of old architecture. Although framed by the oasis, there is no oasis feeling to it; unlike all other oases in this part of Egypt. There are extensive thorn palm, acacia, buffalo thorn and jujube forests in the oasis surrounding the modern town of Kharga. Many remnant wildlife species inhabit this region.

Citizens : Native Khargans are of the Beja races. They speak their own language though Arabic is the dominant language.

Introduction to Kharga Oasis

Geographical view : : Kharga, known to the ancient Egyptians as the ‘Southern Oasis’ is the largest of the oases of the Libyan Desert and consists of a depression about 160km long and from 20km to 80km wide. Today it is often referred to as the ‘Great Oasis’.

Population : Kharga is also the name of the bustling main city of the oasis whose inhabitants now number sixty thousand, including one thousand Nubians who were settled here after the creation of Lake Nasser. The oasis is still growing and the Egyptian government have plans underway to reclaim even more of the desert areas and to offer land and homes to people in the overcrowded Nile Valley as well as to make the area more attractive to tourists. The main source of income in the oasis is from agriculture, the cultivation of dates, cereals, rice and vegetables, which are sent to markets in the Nile Valley. Kharga’s main craft is basket and mat-making from the leaves and fibres of the palm trees.

Geographical view : : Kharga, known to the ancient Egyptians as the ‘Southern Oasis’ is the largest of the oases of the Libyan Desert and consists of a depression about 160km long and from 20km to 80km wide. Today it is often referred to as the ‘Great Oasis’.

Population : Kharga is also the name of the bustling main city of the oasis whose inhabitants now number sixty thousand, including one thousand Nubians who were settled here after the creation of Lake Nasser. The oasis is still growing and the Egyptian government have plans underway to reclaim even more of the desert areas and to offer land and homes to people in the overcrowded Nile Valley as well as to make the area more attractive to tourists. The main source of income in the oasis is from agriculture, the cultivation of dates, cereals, rice and vegetables, which are sent to markets in the Nile Valley. Kharga’s main craft is basket and mat-making from the leaves and fibres of the palm trees.

Historical Background : expeditions into Kharga Oasis go back as far as the Old Kingdom, but little evidence remains in Kharga today of life in pharaonic times. The ancient route into the oasis from Luxor, known as the Luxor-Farshut desert road is currently being studied by the Oriental Institute of Chicago, who have uncovered remains of several early structures and a great deal of pottery from as far back as the Middle Kingdom.

During the Third Intermediate Period, Egypt’s Libyan rulers began to take an interest in the Oases, improving the desert tracks and making an effort to bring the marauding desert tribes under control. From this time onwards Kharga began to prosper and two temples dedicated to the Theban triad were built at Hibis and el-Ghueita during the Late Period.

By then it was securely attached to the Nile Valley and when the Romans came to Egypt they increased the prosperity of the oasis by creating new wells, cultivating many crops and building a series of ‘fortress settlements’ for protection of the caravan routes. These Roman ‘fortresses’ are especially numerous in the Kharga Oasis, where the Darb el-Arba’in (the ‘Forty-Day Road’) which ran north to south between Asyut and the Sudan, was the most important trade route. This was later to become part of the infamous slave-trade route between North Africa and the tropical south.

The chain of at least twenty mud-brick forts vary in size and function, some are large settlements or garrison towns, while others are small desert outposts, but most of them lie close to the road crossing the oasis, following the ancient track. ‘Fortress’ is perhaps a misleading term for these structures, for although it is thought that Roman soldiers were stationed in all of them, they are not all regarded as primarily defensive structures, nor do they necessarily indicate a high level of hostility, at least during the earlier years of the Roman Period. The larger fortresses may have been built on existing settlements, but during Roman times their populations grew rapidly. The Romans went to great lengths to secure water in the oasis, although little is known about how or when the original bore-holes were made – some are over 120m deep and continue to be used today. They also built long underground aqueducts up to 50m deep in the water-bearing sandstone, which must have involved a huge amount of labour. Many of the Roman fortified settlements are situated strategically on hilltops and several, such as Qasr Dush, Qasr el-Ghueita, Nadura, and Qasr el-Zayyan incorporated temples and large communities of people.

The practice of using Kharga Oasis as a colony for exiles continued throughout Roman times and into the Christian era. Many early Christian bishops were banished here and the oasis soon became a refuge for Christian hermits who often lived in isolated tombs or caves in the desert. The Christian population of Kharga quickly grew – many fortresses date from the early Byzantine era – and it was one of the most enduring Christian areas of Egypt, continuing into the 14th century. One of the earliest and best preserved Christian cemeteries in the world can be seen at Bagawat and it contains hundreds of tombs and several chapels still have biblical scenes painted in bright colours.

We do not know precisely when the desert route to Sudan developed. Camels, which were introduced after the Persian invasion, enabled ancient travellers to cover greater distances than they had done previously, but the trade caravans were not popular in the desert regions until the Mamaluke era when rising tolls made the Nile Valley routes too expensive. Two villages at the southern end of the Oasis, Maks Qibli and Maks Bahri were customs posts on either side of the Darb el-Dush, the Nile Valley route which connected with the Darb el-Arba’in. A small mud-brick watchtower at Maks Qibli, known as Tabid el-Darawish, was built by the British in 1893 to protect the trade route.

Lastest News

-

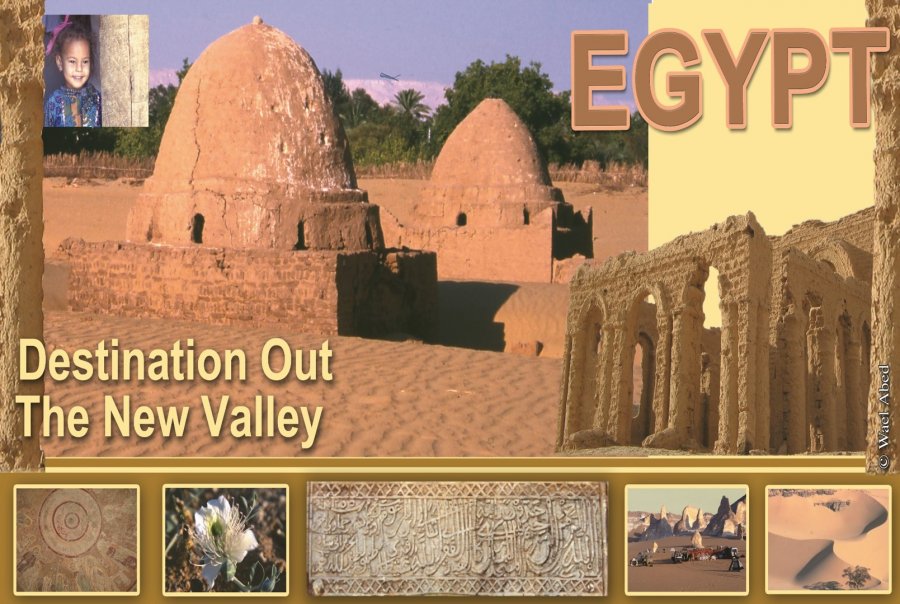

The New Valley in Egypt - Part 1

Shanda Lodge

-

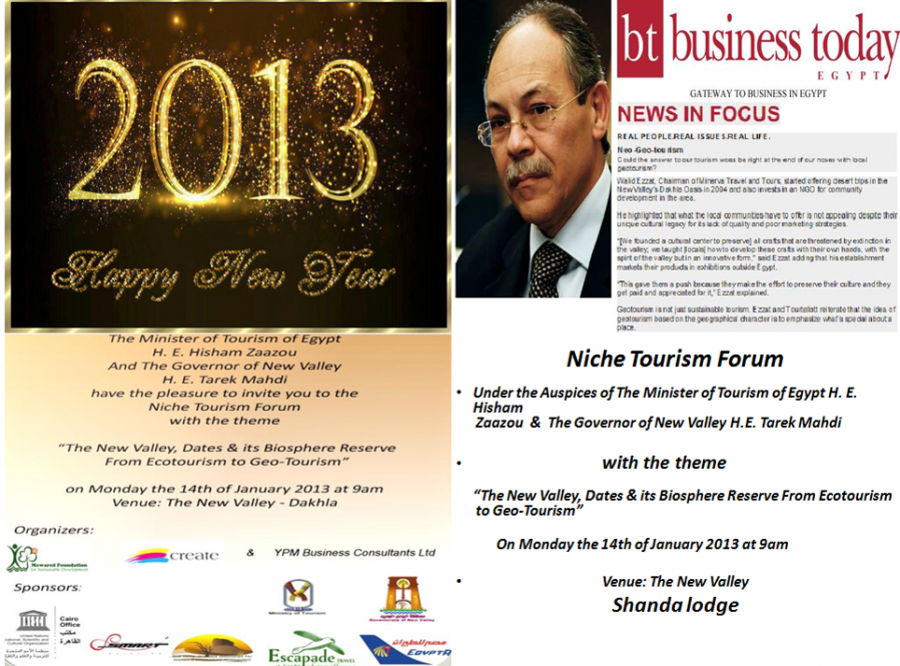

Shanda lodge events

Shanda Lodge

-

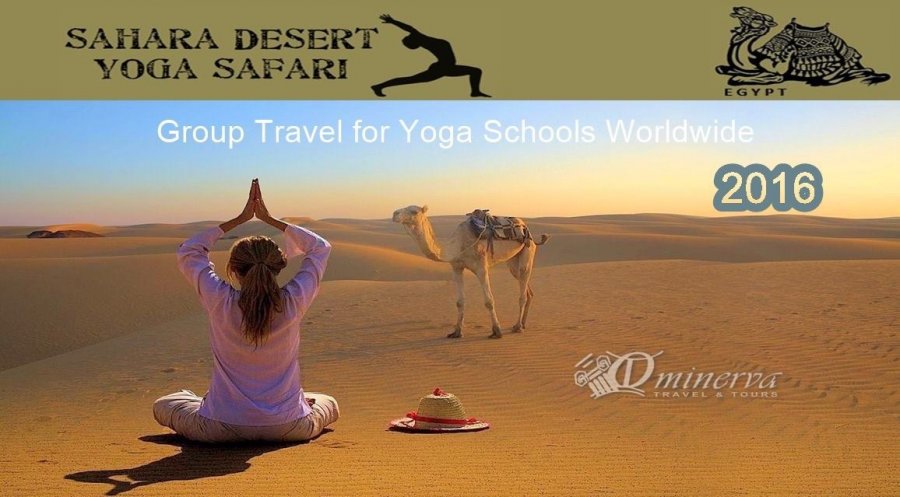

A Magical Escape into Egypt’s Sahara Desert

Shanda Lodge

-

SHanda I T B

Shanda Lodge

-

Flora and Fauna

Shanda Lodge

Email to friend

You need to Login to add item in your wish list

- Facilities

Haze

Haze